One of the joys of raising teenagers is reliving their concert experiences.

Like us, they save their money to buy expensive tickets with obnoxious service fees “for convenience,” and like us, they’re making memories of great shows and good times with friends.

“What was your first concert” will always be a fun ice breaker. Every time I say Duran Duran, someone can hack an old credit card security question. It was a great show at Six Flags Over Texas in 1986 with my buddy Ben and a couple cheerleaders we met at a competing high school. They were our first teenage crush before Missed Connections on the Back Page.

My teenage son Simon recently got swept into a sudden mosh pit at a Catholic youth meetup in Dallas all of all places. Unfortunately a girl got knocked down (it happens), and some Karen mom weaved her way into the group to stop the moshing.

“The hell?” I said. What a devouring mother. While a Christian rock band is hardly the origin story of mosh, I’m sure the music was loud and exciting, and like so many trends of the 1990’s, grunge culture influences today’s teens the way swing dance and sock hop rockabilly did for Gen-X.

I told Simon about the early Lollapalooza and EdgeFest shows I attended at the Starplex Ampitheater in Dallas. With $10 tickets at the gate, the first Lollapalooza show sold out before I arrived. I paid a security guard to let me in via a side gate and wandered around to find my friends Amy, Jackie and May visiting from Longview.

I’ve lost count all the acts I’ve seen there – Red Hot Chili Peppers, Porno For Pyros, Jane’s Addiction, Rage Against the Machine. Pearl Jam played one of their first concerts outside the Pacific Northwest because of all the airtime on 94.5 KDGE, one of the first alternative rock stations in the US under legendary program director, George Gimarc. I remember their hit Jeremy being about a local kid.

Back then, Starplex allowed blankets and coolers for a picnic in the grass hill beyond the covered seats. After dark, all that stuff became fuel for massive bonfires, which amped the band’s energy. Mosh pits formed around these fires with brave kids jumping through them. When security forces brigaded with fire extinguishers, another fire and another pit would spring up across the lawn.

Moshing is universal.

The intensity of the fiery Starplex mosh pits are similar to the hypnotic dhikr prayer chants of Sufi muslims dancing together.

Through a primal need for community, individual men give themselves over to a larger organism, participating in something more powerful than they could muster on their own. People of all faiths make supplications to God through their group identity.

The intensity of a loud Maori haka with its synchronized percussion of stomping, body slaps and guttural roars with wild eyes, jutting chin and flashing teeth taps a similar instinct.

Moshing is a primal awakening of suburban youth. It’s a rite of initiation, bound deep in a violence that is uniquely American. Following our roots as a radical rebel colony, moshing binds individual free will into a unitive creative expression. It’s a tribal group-think, a collective need to be heard.

Not all moshing is a collective expression; I’d argue individuals punching air does not constitute mosh. There is a YouTube video of a chick at a metal concert wandering through a pack of wildly flailing guys, oblivious to the danger she’s placing herself. A young man caught deep in his own ritual, head down, rotated violently from his hunched core and whipped his extended arm to backhand her clean across her skull, likely breaking her nose.

The unharnessed reckless abandon of an individual dancer didn’t survive the 90’s pits… The group would’ve overwhelmed an individual flailing person, or shoved him into the bonfire. He’d have pinballed among us, and forced to conform to the circling group or get beaten down by someone bigger. In the chaos, there is still order.

Mosh pits rarely included women. Brave young women would occasionally jump into the fray without any targeted aggression, like rough housing with older brothers. Inevitably they’d be protected by white-knighting guys who would surround her like a punk kid sister. It made for an odd chivalry where the sacrificial call to heroics is stronger than the need to be heard or to conform.

Why do we mosh?

In his book, The Courage to Create, The existential psychotherapist Rollo May connects rage as necessary to the creative process.

Moshing is a form of creative expression. It’s unfiltered yet ordered, impulsive yet socially restrained. Like all great art, moshing is best expressed within a set of boundaries, literally pressing into the personal space of others who are pressing into you.

Why does this happen?

- We have a deep need to express rage. As we press against the constraints of our existence, we experience a sort of death to ourselves, realizing that we are not in control of our ultimate destiny. Death is core to the human condition; becoming aware of our mortality, our limitations, and the societal structures that stifle individual creativity, we come to grieve the loss of our own life, and therefore our potential. Channeling this rage into a creative ritualistic dance is a transformative and liberating force because it transcends the individual. It stretches into the realm of legacy.

- We must confront our death. Awareness of death is a catalyst for creativity. For the creative person, the realization of our mortality evokes a sense of urgency and a desire to leave an impression, like ancient pictographs in a cave. Confronting death forces us to reflect on our purpose and our values. We’re inspired to create in search of meaning, to affirm our existence.

- We must transcend the anxiety of death. Engaging in creative pursuits helps us transcend our fear of death. When we create an enduring artifact of our life, even the memory of a concert, we’re gesturing toward immortality. We touch a sense of continuity, a significance beyond our physical existence. And for the Christian, a healthy reminder that we are indeed immortal, embodied souls not made for this world.

- We experience a symbolic death and rebirth. The creative process – even the ejaculatory expression of moshing – spans a momentary death and rebirth. Jumping into the pit, being swept into a pulsing circle of fire and sweat, joy and pain, forces one to let go of preconceived ideas, beliefs, and even aspects of their own identity to make way for new possibilities and fresh insights. In a crushing body of fist and elbows, your feet stamping to stay upright, there is no space for anything but the present. Presence is the antidote to life’s crushing anxiety about the regrettable past and foreboding future. The rush of adrenalin and cortisol triggers a Defcon One hyper-vigilance and situational awareness as an amygdalin survival instinct. The alligator brain takes over, and so violently we roll.

Creativity is also an expression of its time. Where abstract artists were a natural evolution of reductive thinking, moshing reflects cold war city kids of the farming and blue collar Silent Generation with uncles and teachers who fought in Vietnam. We faced a bleak future of crime and filth, inflation and job uncertainty, energy scarcity and war, with massive changes in the economy and technology. Concerts exploded with pent up rage, and for a moment, brought people together.

This transformative process that is essential to creative evolution. We rage at our death, and we mosh to be born again.

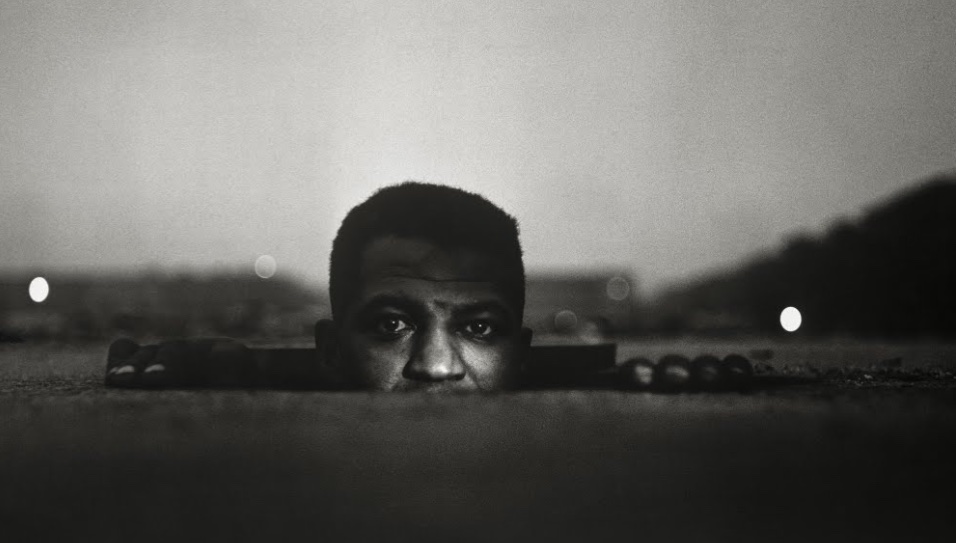

Feature image is from Jay Wennington on Unsplash.