As an executive producer in digital media, I’m drawn tragic and preventable story of the film, Rust. What happened?

I remember how Brandon Lee died after being shot by a prop gun, and the directorial hubris that contributed to the Twilight Zone helicopter crash. We become so engrossed in cinematic story telling, in part, because the of its realism, which can be dangerous to capture.

One of the remarkable outcomes from the Challenger tragedy is that low-level engineers foresaw the risk of o-ring failure, but project leadership failed to recognize the level of risk, and downgraded the priority of remediation. Same with low ranking agents deep in the bowels of intelligence agencies with early concerns of flight school infiltration that failed to rise to meaningful action that might have prevented terrorist attacks on 9/11. History is replete with preventative disaster, or at least mitigated loss, from the Titanic to Halifax, Pearl Harbor to Hurricane Katrina. There were always warning signs.

And so it goes with Rust.

I can’t imagine Halyna Hutchins’s husband who is undoubtedly reeling in early stages of grief marked by disbelief after the accidental shooting of his wife by Alec Baldwin. Apparently they spoke by phone, shortly after the shooting, where he said the actor expressed confusion and a remorseful conciliatory tone.

I’m reticent to cast blame on the inexperienced armorer Hannah Guiterrez Reed who admitted her inexperience on set, though she had been deep knowledge of firearms, and had been on many sets with the legendary armor Thell Reed, her father. On the set of Rust, she split her attention between being armor and prop master, a resourcing issue overseen by the film’s producer, who also happened to be the shooter. And remarkably, earlier in the day, members of the film crew quit in protest of unsafe working conditions.

How can this be? How do we mitigate risk on mission critical work?

Fundamentally, I think the answer is summoning the courage to speak truth, no matter how difficult. Or at least not lie, by commission or omission.

I’m practicing this lesson myself. I have a personal tendency to not speak up when I intuit my words won’t matter. I’ve long dismissed this dreadful practice as being staunchly Gen X, embracing the angst of my low population sandwiched between Boomers and Millenials. We’re old enough to know The Greatest Generation, and lived through the real threat of nuclear annihilation. Our culture, music, films and literature express underlying frustration with the insufferable state of being. Gen X wanted change, not tearing institutions down.

Our solution? Shut up, it doesn’t matter, carry your cross and continue. Raging against the machine

I’ve come to learn we’re wrong. Or at least not quite right. Our eff-it attitude is rooted in helplessness and fear. Fear turns to anger, then resentment, contempt and ultimately nihilism. We care too much to let the world fall into cynicism and despair.

Fortunately, we’re smart enough to not dismiss sage advice, but I fret our timeline is too small. It’s a folly for a modern man to ignore his ancestors, to assume we know better than those who dreamed big with less energy and technology, who laid the foundation for everything we know and have today.

Raging against the proverbial machine hasn’t been sufficient. We have to articulate problems as we see them. We have to listen carefully, in humility, and hone our disposition toward justice and mercy, to develop the intelligence and courage necessary to avoid pitfalls.

And so it went with the production of Rust. Emphasis is mine:

This tragedy is not just down to cost-cutting measures or crew fatigue. Wolf says movie sets can be so intimidating, staffed with young crew members who are star-struck or cowed by a demanding director or just thrilled to be working in the industry, that most would never speak up.

From the NY Post. Steve Wolf is a firearms and special effects expert in Hollywood.

In Pursuit of Truth, Beauty and Good

The ancient Hebrew texts of Sirach offers timeless counsel on the practicality of speaking truth coupled with wise silence.

One is silent and is thought wise; another, for being talkative, is disliked. One is silent, having nothing to say; another is silent, biding his time. The wise remain silent till the right time comes, but a boasting fool misses the proper time.

Sirach 20:5-7

The knowledge of the wise wells up like a flood, and their counsel like a living spring. A fool’s mind is like a broken jar: it cannot hold any knowledge at all. The mind of fools is in their mouths, but the mouth of the wise is in their mind.

Sirach 21:13-14,26

Written 2200 years ago, this sage advise doesn’t mean wise people need to be silent. On the contrary, they need to speak up, and properly discern the right time to do so.

Sirach captures the idea of capital-T Truth as a universal spirit, originating in ideas and intuition, and animated in our communication. We participate in the advancement of Truth by speaking it, even roughly, to bring reality to life.

My favorite leaders in business are those who have the courage to listen, to encourage dialogue, and to share bold opinions. Personally, I flourish in these environments because I believe an idea can come from anywhere. Truth has a way of revealing itself in the collective good of earnest people pursuing a noble goal.

I’ve watched organizations and micro-cultures lose the core value of dialogue. In these environments, I’ve grieved the loss of my own voice and others like me who drown in a sea of prideful certainty.

You can spot loud cowards when they thwart inspiration. They’ll uprooting the very source of potential, with skepticism and snark. They offer bad advice unsolicited, and lead with criticism. If an idea is incomplete, they’ll not iterate. They withhold encouragement, let alone a better way. They lack imagination. They see the world in terms of scarcity instead of abundance. They see people motivated by power, not purpose. They murder ideas with little daggers like sales forecasts and weak budgets, senseless deadlines and quarterly results.

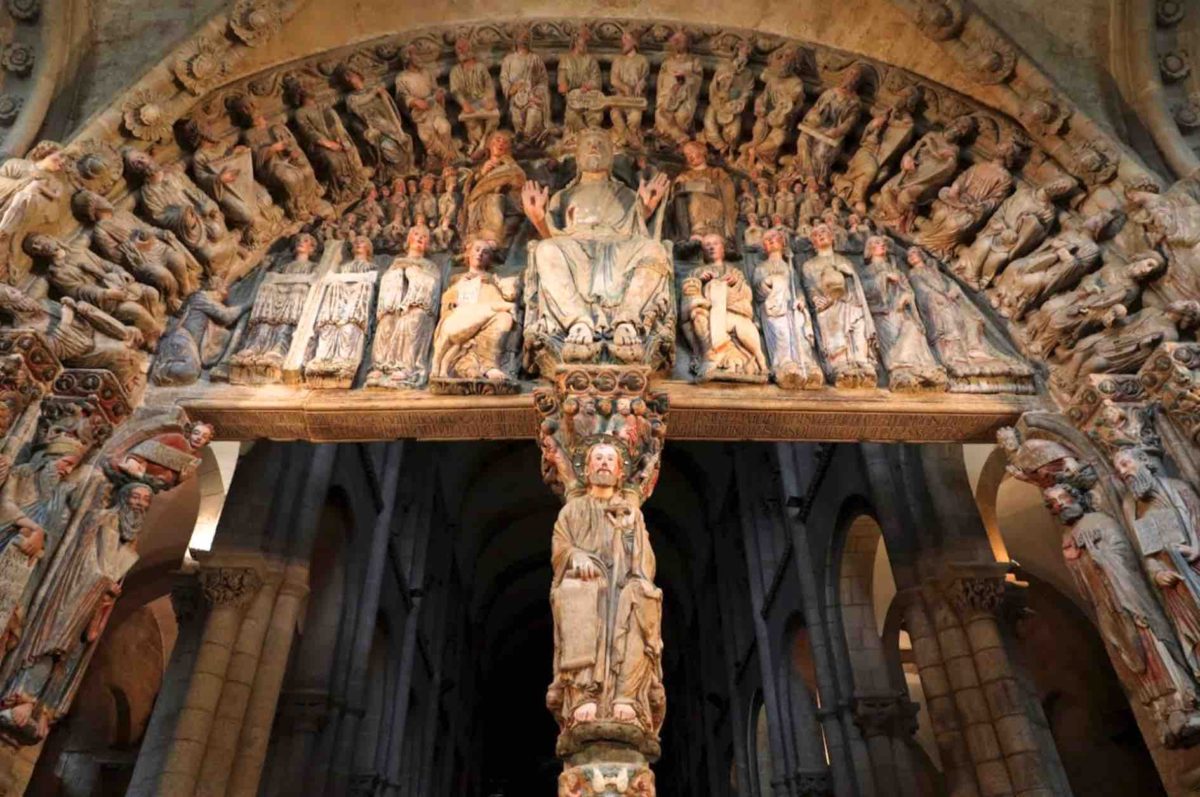

To wit, beauty is crafted in order. We don’t build great cathedrals and engineering marvels without systems. Knives are wielded by madmen and master chefs, to cut and to kill.

We bring about Beauty in Truth for the common Good.

Feature image is The Pórtico de la Gloria, en la Catedral de Santiago de Compostela created in 1075. Since the 9th century, countless pilgrims have walked the “camino” Way of St. James the Great to visit the shrine and burial site of the apostle. Santiago de Compostela is the capital city of Galicia in northwestern Spain. The Old Town district is designated a UNESCO World Heritage Site. Photo by Axencia Turismo de Galicia.